‘Imagine tons of footballs but no football fields’: Desperate bikers build illegal tracks in Brisbane bush

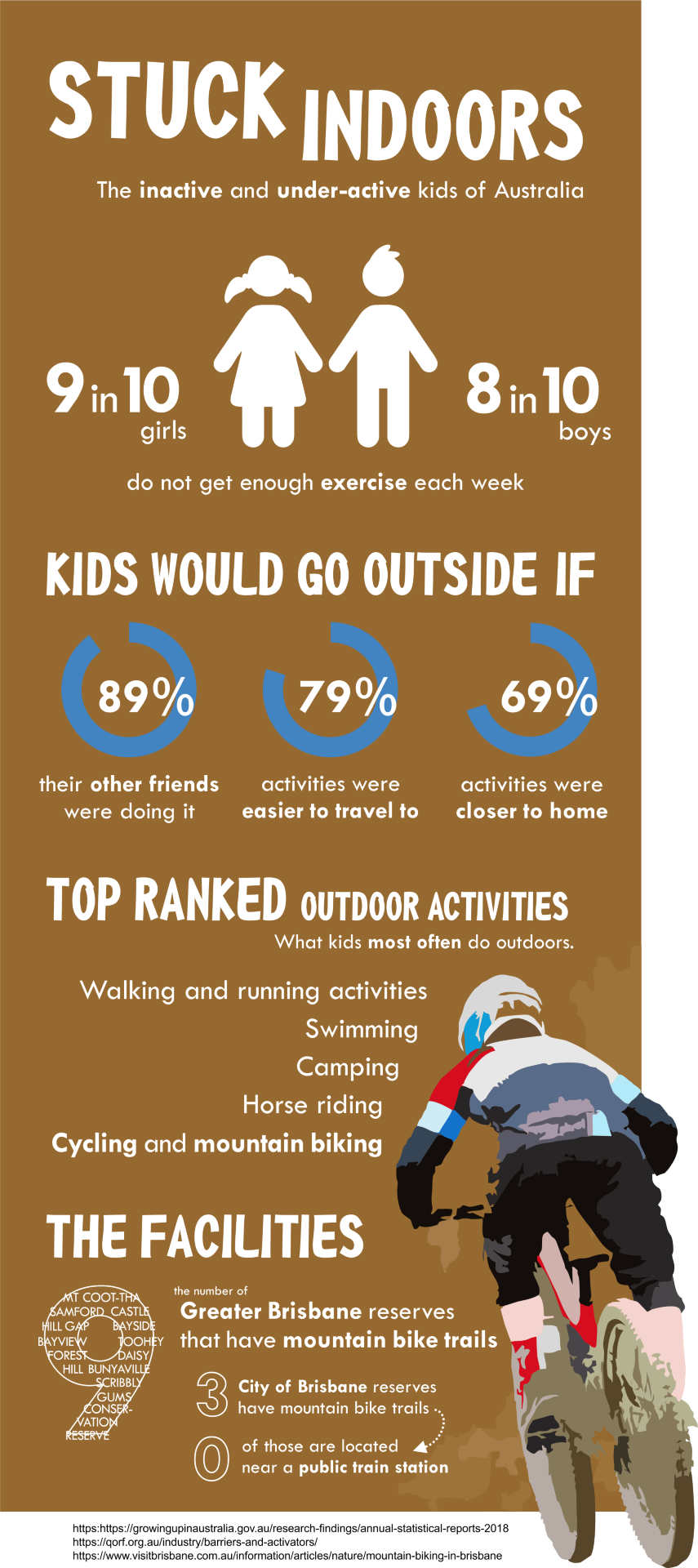

Children as young as 12-years-old are among those facing council crackdown over illegal bike trail building in reserves across southeast Brisbane.

Bike riders have built dozens of dirt mound jumps, knocked down endangered trees and cut steep tracks through ravines in bushland where riding is prohibited, including at Seven Hills Bushland Reserve, White Hills Reserve and Belmont Hills Reserve.

Seven Hills mother-of-two Suzi Robertson said children had to build their own trails as existing bike facilities at Mt Coot-tha and Daisy Hill were too far away.

“My child in lockdown with his 30-minute break between lessons used to be able to hop on his bike and ride in the bush and be back for the next lesson,” said Ms Robertson.

“There is nowhere else where they can take their bike out like that.”

But recent mountain bike activities have scared off wildlife, destroyed native plants and caused ankle-deep cavities and cracks to develop across the conservation zones.

Brisbane Off-Road Riders Alliance (BORRA) President Dan Crawford said there is a need for more mountain bike facilities in fast-growing residential suburbs.

“You’ve got the footballs, but no football fields,” said Mr Crawford.

“Mountain bikes are getting sold, and councils and governments are encouraging us to ride bikes, but at the moment they’re not meeting supply.”

The council has since flattened several dirt jumps and installed surveillance cameras in the Seven Hills reserve, while an unknown group has placed logs, boulders and concrete pylons across tracks used by bikers.

Cavendish Road State High School student Dylan Wildman said a hard approach to mountain biking won’t stop youth from building trails.

“Kids are going to find new and different ways to do the same stuff: riding bikes in new places, building new trails,” he said.

“The solution is to build sustainable trails that are going to last a long time and going to still support the natural environment.”

Mr Wildman has founded a mountain biking club at his school to organise trips to bushland reserves, which has since grown to 40 members.

Outdoors Queensland executive Dom Courtney warned that a hard crackdown on youth bikers would discourage children who have been making the effort to be physically active.

“It’s really not good enough to go ‘nah, you’re not allowed to do that activity in that place’. We need to understand why,” said Mr Courtney. “There’s mountain biking allowed at Mt Coot-ha and there’s some awesome mountain bike trails there, but not everyone can get to Mt Coot-tha easily to go for a ride.”

One report from the Australian Institute of Family Studies found 85 percent of Australian children did not meet the recommended 60-minutes of exercise per day.

“Let’s not forget that the youth and young people are an important part of all our communities,” he said.

Mountain biker Akira Garrett, 15, said he wanted to work with authorities to build bike jumps that wouldn’t damage the environment.

“[The council] were going to talk to me about how to sustainably create mountain bike trails in Brisbane, and the email I got back from [their] office was just telling me to stop.”

“Nobody’s working with me, nobody’s helping me prevent this.”

BORRA president Dan Crawford said illegal trail building made it more difficult to work with authorities to expand the Brisbane trail network.

“Mountain bikers generally are very environmentally conscious – it's embedded into the DNA of the sport,” said Mr Crawford.

“We’re all here to save the forest, to save nature. We don’t want to be riding on concrete paths or concrete jungles,” he said.

A survey conducted by BORRA found environmentally friendly and sustainable trail design was ‘important’ or ‘very important’ to over 95 per cent of Brisbane mountain bikers, more important than trail variety or public transport access.

“Mountain bikers and catchment groups should really be on the same page,” said Mr Crawford. “We’re pushing for the same things.”

A conservationist affected by illegal trail building agreed with Mr Crawford but said reserves at Seven Hills and Whites Hill would be too small for mountain biking.

“Anything you did in here would have a proportionally large impact on the environment,” said the conservationist, who asked not to be named.

“You can open it up and some people will be responsible, but a hell of a lot of people won’t be.”

The conservation group had shovels, pickaxes and wheelbarrows stolen after their tool shed was smashed in last month.

“A resolution has to be found,” the conservationist said.

“That’s all I can say, and I honestly don’t know what it [the solution] is.”

Council plans to expand Brisbane’s trail network were due to be released this month but have since been delayed.

However, Mr Wildman said he was optimistic about the future of mountain biking in Brisbane.

“We want challenges,” he said. “What’s your next challenge, what’s your next goal?”

“That’s at the heart of what mountain biking is about.”